National case studies: Case of Poland

An important element of the Egruien project is in-depth sectoral analysis. As part of WP2, we analyse national historical case studies and use them to develop a theoretical framework.

We will regularly publish the results of our findings. We are starting with Poland, which represents the countries of Central and Eastern Europe.

From coal to cars: the economic transformation of Upper Silesia (1990–2024)

When we think about the biggest economic changes in Poland over the last few decades, Upper Silesia – once the heart of the coal and heavy industry – is one of the most vivid examples. The changes that have taken place in the region say a lot about the broader context of Poland's transformation.

Before 1989, Poland was dominated by a centrally planned, state-controlled economy. Industry was outdated, wages were not linked to productivity, and by the end of the 1980s, the system collapsed under the weight of debt and hyperinflation. After 1989, the government introduced ‘shock therapy’ consisting of price liberalisation, privatisation of state-owned enterprises and cuts in subsidies and grants. This stabilised the economy but caused a number of difficulties, including on the labour market, where unemployment rose to over 20% in 2003.

Poland's accession to the EU in 2004 marked a turning point. Poland received almost €250 billion from EU funds. GDP doubled, unemployment remained low, and Poland ranked among the fastest growing economies in the EU, just behind Ireland and Malta. The structure of the economy has changed radically: services now account for around 60 per cent of GDP, industry around 30 per cent and agriculture only 2-3 per cent. The Polish labour market is characterised by flexibility. Many people are self-employed or work on fixed-term contracts, and although the number of temporary workers has declined over the last decade, precarious employment remains widespread. At the same time, unemployment has fallen to one of the lowest levels in Europe, currently standing at around 3%. Trade union membership is weak, collective bargaining rather rare and mainly limited to the public sector. Employers' organisations are stronger but fragmented. Social dialogue mechanisms exist at the sectoral level, but their effectiveness is limited and often depends on the political context rather than balanced negotiations. As a result, the government dominates labour market policy-making.

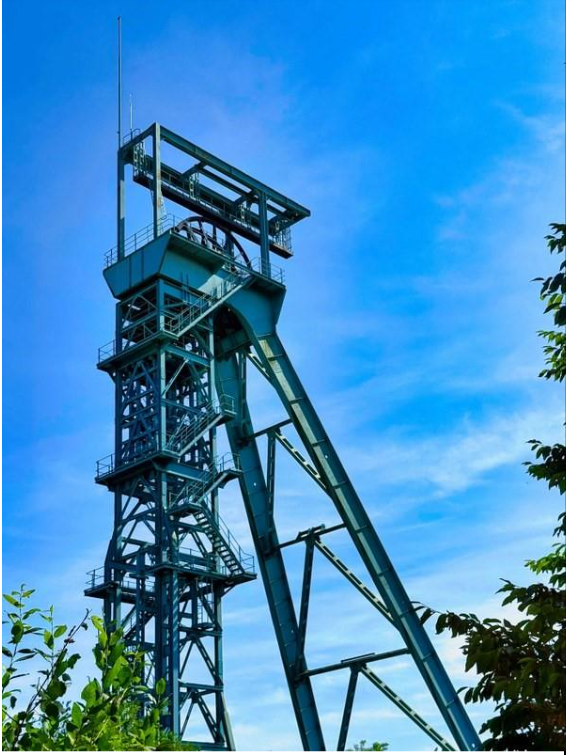

Upper Silesia provides a good lens through which to analyse changes in four key sectors of the EGRUiEN as the region has undergone one of the most striking transformations. For decades, the region was dominated by the coal and energy industries. Once heavily dependent on coal mining, the region has undergone several waves of restructuring since 1989. Mines have been closed, employment in mining has fallen from almost 400,000 to less than 100,000, but coal still accounts for the majority of Poland's energy production.

The automotive industry has become the second most important industry, but it is also characterised by instability and strong dependence on foreign investors. At the same time, new industries are developing, such as finance, real estate, IT outsourcing and global business services. The European Green Deal is already driving another wave of change, with a gradual transition from combustion engines to hybrid and electric cars.

The transformation also had a social dimension. Workers and trade unions had limited influence on key decisions, but their voice still mattered. Through strikes, protests and social dialogue, they shaped part of the debate on how the region should develop.

In the energy sector, studies show conflicting assessments of collective agreements. Some see dialogue between trade unions, employers and the government as a positive force supporting productivity and competitiveness. Others argue that social dialogue has been abused to delay difficult reforms, supported by clientelist networks and the bargaining power of miners. This has created a system in which public funds have covered the losses of unprofitable mines for decades. Trade unions in the mining sector remain strong, giving workers a powerful voice in shaping restructuring. Negotiations have sometimes resembled cooperation aimed at preserving jobs, but overall results have been mixed, as the country still covers around 70% of its energy needs with coal.

The care sector presents a different picture. After 1989, it underwent waves of liberalisation and partial privatisation. Employment in the health service currently stands at over 750,000, but the workforce is ageing, with over half of doctors and two-thirds of nurses aged over 50. Trade unions in the healthcare service are relatively strong compared to other sectors, covering around 20% of workers, and large organisations of nurses and doctors are active in protests. There have been repeated strikes, including by young doctors and nurses demanding better pay and working conditions. Despite reforms, the health service continues to suffer from staff shortages, underfunding and a widening gap between public and private services, which, rather than resolving the chronic crisis in public services, is exacerbating it.

Transport reflects yet another model, one of almost complete liberalisation. Since the 1990s, the number of taxi companies and licences has risen sharply, many drivers are self-employed, and the sector is fragmented and unstable. Deregulation has encouraged the spread of unlicensed operators and, since 2014, global platforms such as Uber and Bolt. These companies rely on precarious contracts and migrant labour, with little regulation and no tradition of collective bargaining. Protests by professional taxi unions are common, but social dialogue is virtually non-existent. Recently adopted legislation, including the so-called LexUber, attempts to impose basic licensing and safety requirements, but the sector continues to face legal loopholes and widespread abuse.

In Upper Silesia, the combination of mine closures, factory restructuring and poor public services has caused serious social problems. In the 1990s and early 2000s, heavy industry experienced mass layoffs, leading to poverty, social exclusion and migration. Women and children were particularly affected, and sociologists describe the feminisation of poverty in the region. Over time, thanks to the support of the Katowice Special Economic Zone, new jobs were created in the automotive and service industries, but many of these were less stable and less well paid than the traditional mining jobs they replaced.

At the company level, the contrast between Jastrzębska Spółka Węglowa and Polska Grupa Górnicza shows different paths of development. JSW, which focuses on coking coal for steel production, has proved more efficient and profitable, while PGG, a state-owned supplier of energy coal, has survived only thanks to consolidation and state support. Both companies are strongly unionised, and their restructuring is shaped by frequent protests and complex negotiations.

The automotive industry in Upper Silesia followed a different path. The Fiat and Opel plants, now owned by Stellantis, became central to the region's economy. However, they too have gone through multiple cycles of layoffs, production cuts and restructuring. Workers have often resorted to strikes and protests when dialogue failed to produce results. The transition to electric vehicles introduces new uncertainty, as most Polish plants still focus on combustion engines. Investments in hybrid and electric vehicle production are starting, but component factory closures and job cuts are continuing.

The history of Upper Silesia reflects Poland's broader journey from a coal-based economy to a modern and diversified economy, from state planning to the dynamic growth of the EU market, and from economic turmoil to one of the most resilient economies in Europe. It is a transformation full of challenges, but also lessons for other regions facing industrial change.

Overall, Poland's experience highlights the complexity of economic transformation in a post-communist context. A flexible labour market and foreign investment have contributed to economic growth and job creation, but weak social dialogue and limited trade union influence have left many workers in a precarious situation. The history of mining and the automotive industry in Upper Silesia illustrates both the potential for renewal and the costs of restructuring, where government decisions and global markets have a greater impact on the future of the labour market than collective bargaining.